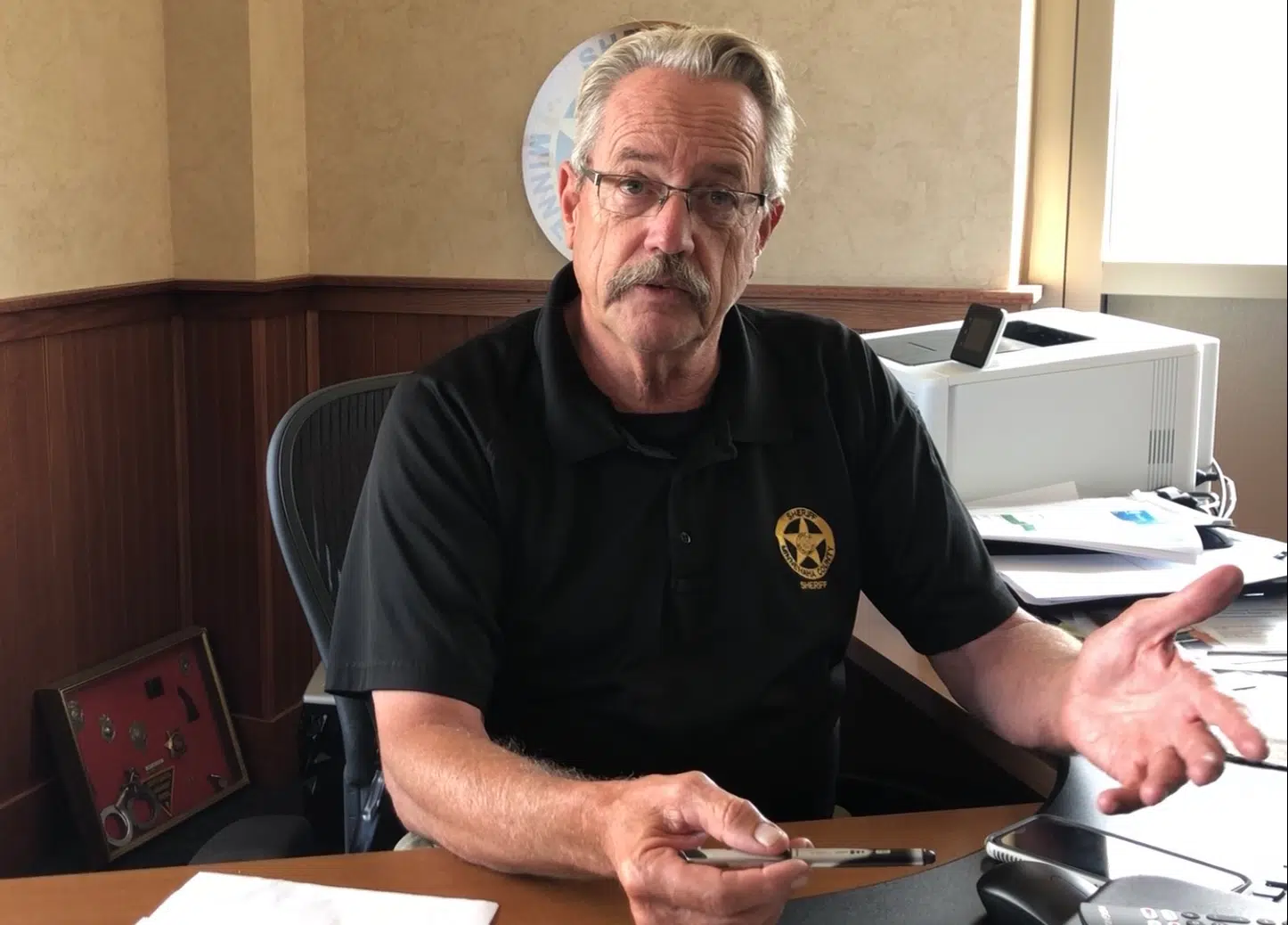

Minnehaha County Sheriff Mike Milstead. Photo: Danielle Ferguso, South Dakota News Watch

By Danielle Ferguson, South Dakota News Watch

South Dakotans battling addiction to opioids are increasingly relying on medication-assisted treatments to overcome their cravings for the dangerous drugs and to avoid potentially deadly overdoses.

However, access to the life-saving medications is limited in South Dakota and some physicians in the state are reluctant to prescribe the drugs that have shown great promise in overcoming opioid abuse. Meanwhile, addiction experts and some law enforcement officials are trying to break down barriers to wider use of the treatments.

Medication-assisted treatments for addiction use drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to alleviate withdrawal symptoms and relieve cravings resulting from chemical imbalances in the body. As the prescription drug treatments take effect, physical symptoms of addiction will ease, allowing patients to focus on work, relationships and their health. The medications can be taken on a short-term or long-term basis and are increasingly viewed as a successful method of improving the lives and health of people addicted to opioids.

Opioids are a class of addictive drugs that include the illegal drug heroin, synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, and pain relievers legally available by a prescription. Opioids, which have devastated thousands of lives in other states, are not the most widely misused drugs in South Dakota but they are responsible for a majority of fatal overdoses, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nationally, 70% of all overdose deaths involve an opioid.

While the treatment has been available for decades, access to medication-assisted treatment has gained traction in South Dakota only within the past five years. More than 90,000 drug overdose deaths are estimated to have occurred in the United States from September 2019 to September 2020, the highest number of overdose deaths ever recorded in a 12-month period according to the CDC. Opioid fatalities increased by 55% over the previous 12 months.

South Dakota experienced a more than 20% increase in all drug overdose deaths from 2019 to 2020, according to an emergency health alert from the CDC in December.

Medication-assisted treatment is considered the most effective way to treat addiction, known as opioid use disorder.

About 90% of patients who receive the treatment remain free from addiction for more than two years, according to the FDA. Nearly 100% of all people who solely go to traditional drug treatment or rehabilitation will relapse, and many overdose.

“A lot of patients have told us it saves their life,” said Dr. Dan Felix, a licensed mental health therapist and director of behavioral health at the Sioux Falls Family Medicine Residency program. “It prevents overdose and relapse. We take a de-stigmatized approach to treatment.”

Janine Crowe, a 35-year-old resident of Sioux Falls, was addicted to opioids for more than a decade and could not shake her addiction until she began a treatment plan that included medications to ease her cravings for painkillers.

“It helps me stay sober,” said Crowe. “It helped with my anxiety. It got me out of the mind frame of using drugs.”

Medication-assisted treatment can be provided by physicians, physician assistants and nurse practitioners who undergo additional training to be certified with what is called an “X Waiver.” Counseling and other care services are usually part of the overall treatment plan, but the medication itself is effective in curbing cravings, Felix said.

Methadone, an opioid, has been used to treat addiction to other opioids for more than 50 years, but it is potent and can only be taken through certified programs. The only facility in South Dakota that can dispense methadone is the Sioux Falls Treatment Center.

Buprenorphine is a more common, safer alternative. It partially activates opioid receptors in the rain, often reducing drug use and protecting patients from overdose by reducing cravings. Buprenorphine, which can be prescribed by a primary care physician, does not put patients in the euphoric and impaired state that makes opioids ripe for abuse.

Some critics of the treatment say it is simply “trading one addiction for another,” creating a difficult-to-change negative stigma around addiction treatments that some patients and doctors still cling to, Felix said.

“This is replacing one drug for another; it’s replacing one that’s going to kill you for one that’s going to save your life,” Felix said.

Between June 2019 and May 2020, the Center for Family Medicine provided MAT education to 58 medical providers or medical students in South Dakota, 10 of whom eventually obtained waivers required to administer the opioid treatment medications.

In 2016, only about 12 of South Dakota’s 66 counties had at least one health care provider who could prescribe the most-used medication to treat opioid use disorder, buprenorphine, according to the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy. Nationally, fewer than 1 in 10 people have access to this type of care.

“MAT is the gold standard for opioid addiction treatment,” said Dr. Stephen Tamang, a family physician for Monument Health and founder of Project Recovery in Rapid City. “When I started (practicing), there was a big dearth of access here. There were no significant services at all.”

Project Recovery, the state’s largest telehealth addiction recovery program, has experienced rapid growth in service requests each month over the past year, Tamang said.

The number of prescriptions doctors give for opioids as a painkiller has been on the decline since 2012, but use and overdoses have been on a steady increase, mostly because of illegal manufacturing and selling. Some drugs sold on the streets are laced with powdered fentanyl, a substance up to 100 times more potent than morphine. Humans can die from just 2 milligrams of fentanyl, equivalent to a few grains of salt, according to the DEA.

“A lot of those overdose deaths are attributed to opioids, fentanyl,” said Minnehaha County Sheriff Mike Milstead. “That has a huge impact on people’s lives and families. A lot of the time, these people aren’t trying to kill themselves. These are accidental overdose deaths.”

The Minnehaha County Jail will soon become the first facility in the state to treat inmates with opioid addiction medications after they arrive. The jail has allowed inmates who are already on the treatment to continue it, and has long allowed pregnant women to start or continue the treatment. Previously, the Yankton County Jail was the only jail that allowed patients to continue on the treatment, according to the Center for Family Medicine.

Crowe, the Sioux Falls resident, is now in her last phase of drug court. She heard about medication-assisted treatment through other women who were also staying at the New Start treatment center.

“I said, ‘I don’t know if I can take this anymore,’” Crowe said. “They said, ‘Why don’t you try medication?’ I said, ‘There’s medication?’”

Crowe’s addiction to pain pills and methamphetamine started in 2008, after her husband was killed by a relative on the Crow Creek Indian Reservation. She sought mental-health care at an Indian Health Service clinic, but was not provided antidepressants, she said. She sought comfort at a relative’s home. That relative gave her the opioid Darvocet to manage pain from an infected ingrown toenail and Crowe enjoyed the euphoria that came with the pain relief.

She completed six months of traditional treatment, but relapsed shortly after being released.

“My heart was in it, but I couldn’t get the drugs off my mind,” she said. “Everything you do is drug-related. The reason you get up is because you’re going to look for a drug.”

She went to Falls Community Health and was given Suboxone in the form of a tablet that dissolves under the tongue. Within hours, she noticed her cravings cease and didn’t feel the flu-like withdrawal symptoms she would normally feel if she went without using.

“I didn’t want tramadol anymore,” she said. “I didn’t crave anything. A weight was lifted off my shoulders. It was a relief. I take one tablet three times a day.”

Crowe now has a job, an accomplishment she would have thought unobtainable two years ago.

“I used to be on the streets, never held a job,” she said. “Now I work. I’ve been sober for almost two years now.”

Comments