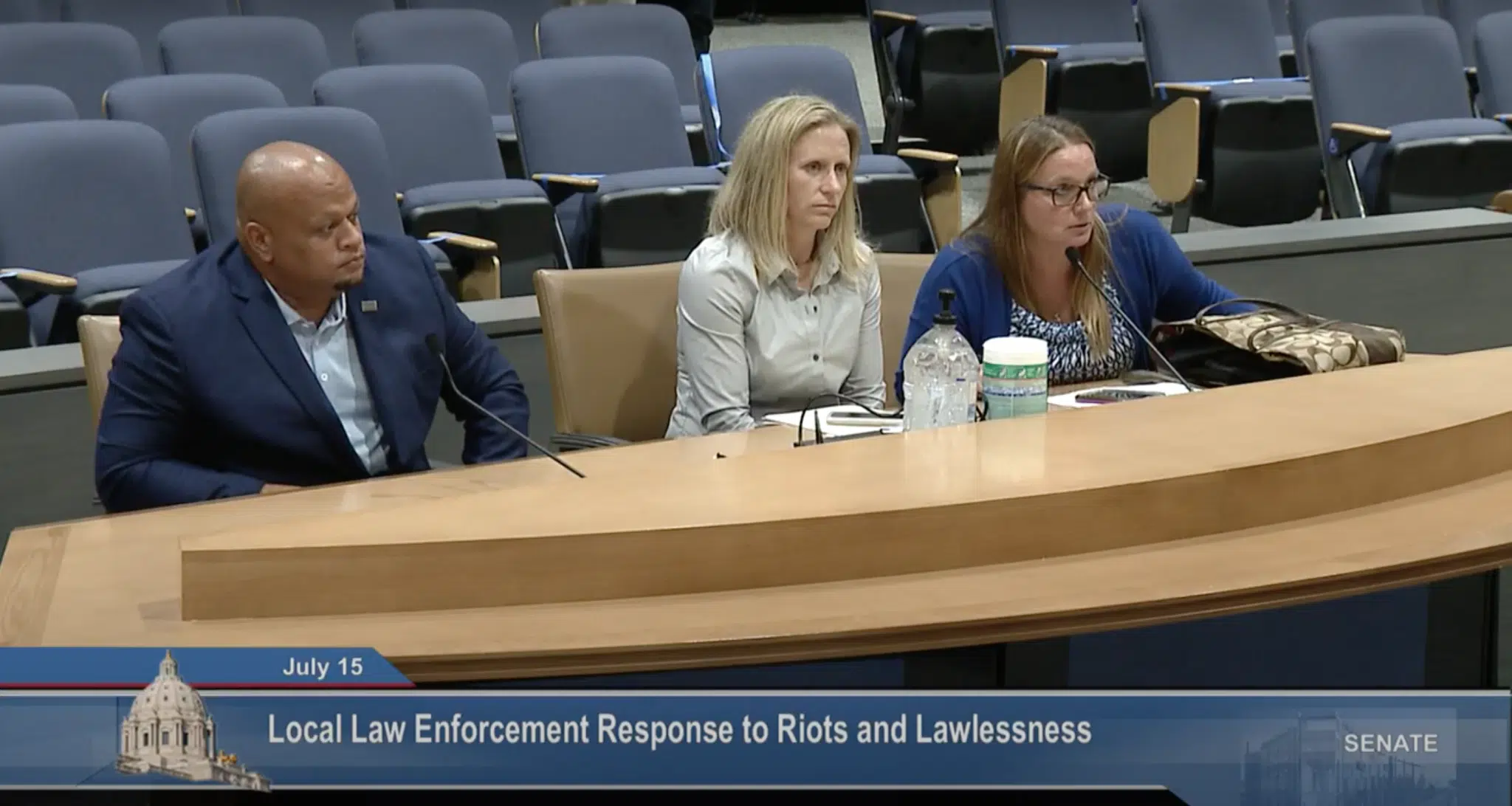

Sgt. Anna Hedberg, center, testifying before a Senate committee this summer. Hedberg says statements from the Minneapolis City Council have made policing harder amid rising violent crime. Photo from the Minnesota Reformer.

MINNEAPOLIS (KELO.com) — When the 35W bridge collapsed in 2007, Anna Hedberg was 24 years old and six days into her job as a Minneapolis Police officer. She rushed to the scene with her training officer, and climbed under rail cars to get to people in their cars.

“Seems like a lifetime ago,” she said of that day.

The 5-foot-3 cop would go on to work in north Minneapolis for more than 10 years and make sergeant doing a job she loved.

“I liked arresting bad people,” she said. “I liked putting the criminals in jail.”

Then she was elected to be one of the directors of the Police Officers Federation of Minneapolis.

And after George Floyd died under the knee of her colleague, she found herself in the spotlight, this time having to answer for former officer Derek Chauvin.

Ever since then, she said of policing Minneapolis: “It’s just bad.”

She spoke while sitting in her car in the garage, staring at bikes and thinking about all the hate mail she’s gotten in recent months. About the “serious arguments” she and her husband have gotten into “about what I do.” About being called a “crybaby Minneapolis cop” in a City Pages story for choosing not to live in the same city where she works because she wants to avoid running into people she has arrested in the grocery store with her daughter.

Today, sometimes it feels like the Police Department is collapsing under the weight of Floyd’s death — or perhaps under Chauvin’s knee.

Under pressure from constituents and activists, nine Minneapolis City Council members vowed to “begin the process of ending the Minneapolis Police Department” after Floyd’s death. The voters may have a chance to radically transform the department through a charter amendment next year.

The aftermath has been ugly. A wave of gun violence followed protests and has continued. 911 calls went unanswered, response times slowed, and council members and constituents accused police of deliberately pulling back to make a point.

Minneapolis recorded its 72nd homicide Sunday when a teenager was shot during a robbery in Uptown, almost doubling last year’s pace. The 5th Precinct recently warned of an increase in “persistent” and “very troubling” street robberies and carjackings, often by teens. Violent crimes are at the highest level in five years.

Are the police pulling back? Or are they overwhelmed, outgunned and outmanned? We’ve heard little from Minneapolis Police officers thus far, but Hedberg spoke expansively in a Reformer interview.

Pulling back?

Slower response times indicate police have been less responsive to calls for help since Floyd’s death, but Hedberg said police have not pulled back, even though the phenomena has been documented elsewhere around the country after high-profile police killings.

“We’re not skirting our duties to the 911 callers whatsoever,” she said. If people call 911, police are responding in priority order. If someone is shot, stabbed or beaten, their call takes priority over, say, a stolen vehicle. While responding, the officer may get called to another assault, or armed robbery, and on and on until eventually they get to the car theft.

“They’re out there trying to do their jobs,” Hedberg said.

The only place police are not responding to calls is the “autonomous zone” at 38th and Chicago, where Floyd died. “They have armed people around 38th and Chicago, primarily drug dealers or gang members,” Hedberg said. “That’s their territory.”

She acknowledged police are less likely to stop a drug deal on a corner or make proactive traffic stops now, because they’re stretched too thin and more hesitant about putting themselves out there.

She painted a scenario: Let’s say police are called to check on a Black Minnesotan.

“Within 10 minutes there could be 15 to 20 bystanders with cameras, yelling “(Expletive) you, (expletive) 12!” she said, the number 12 referring to a nickname for police.

When politicians say the police are corrupt, she said, criminals take that as a green light to have a “free-for-all.”

“Criminals know now they just show up in groups and make it nearly impossible for us to respond and take control of a situation,” she said. “It’s not that the police are pulling back, it’s that the criminals have been emboldened by the statements made by our failed elected officials and our city leaders.”

City Council member Steve Fletcher found it “odd” that Hedberg blames the council.

“It’s a very convenient narrative for someone who doesn’t want to change and who in fact actively resists change to try to pretend that the murder of George Floyd is not the reason the police are losing legitimacy in the eyes of many of our residents,” he said. “And that years of profiling and harassment and ketamine injections and lost rape kits… aren’t.”

He said there have been flare ups for decades where people have raised objections about policing, and the union’s response has been to resist change and “let it pass.”

“We’re just beyond the point where we can let this pass. This is way bigger,” Fletcher said. “If the federation won’t admit there’s a problem, I’m really not sure how they can be part of the solution.”

Council Member Jeremiah Ellison sarcastically asked if the union is also blaming the council for rising gun violence in other cities across the nation, referring to a spike in shootings elsewhere. People have lost faith in the police due to repeated police killings, not the council’s comments, he said. Speaking before the election, Ellison said the union was using these critiques to deliver Minnesota to President Donald Trump.

Minneapolis residents say when they ask police for help, officers sometimes tell them to take it to the City Council. Residents and members of the City Council say that response is a peevish abdication of responsibility.

Hedberg acknowledged officers have told the public to alert the City Council if they don’t like how things are going.

“I’ll say, ‘Call your council person and tell them,’ ” she said. “We have a group of 13 (council members) that wants a police force of utopia and maybe 100 cops to handle violent crime.”

Even gang members have begged cops to “come out and start stopping people,” she said. “But it’s so difficult to do that knowing they can turn into a crappy situation really fast.”

Hedberg was recently helping out on Nicollet Mall, where a person wanted for burglary was discovered in a group of about five, she said. It took six cops to arrest the suspect, including Hedberg, who stood with her back to the arresting officers, monitoring the situation, making sure it didn’t spiral out of control.

Although some people are happy to see police and wave and smile, others yell at them, flip them off and try to get an emotional reaction, she said.

Recently police were called to Peavey Park after a man was robbed and pistol-whipped. Two cops found the suspect, and were immediately surrounded by a hostile crowd, and then the victim said he didn’t want the man arrested, Hedberg said.

“I’m not saying the video of George Floyd didn’t look bad and there shouldn’t have been any anger or outcry,” Hedberg said. “It was terrible to watch. I can understand the rage that people felt, the anger, the hurt… but it’s going to have to play out in the courts, that’s why we have the judicial process. Because at the end of the day, we’re all citizens.”

Morale at all-time low

In late September, Hennepin County Deputy Sheriff Matthew Hagan, who is president of the Minnesota Fraternal Order of Police, told Vice President Mike Pence that in his 21 years in law enforcement, he’s never seen such poor morale.

“You don’t think it’s gonna get any worse and it keeps getting worse,” he said. “I’m hearing a lot of my friends in Minneapolis and other cities, they don’t even want to go to work anymore. They said they get sick to their stomach before they have to go into work because they know there’s no support there.”

Hedberg agreed police morale is at an all-time low, which she believes is a direct result of the City Council’s push to defund the Police Department.

“Try going to work every day thinking that the City Council doesn’t really want you to go to work,” she said.

(Although the City Council has the power to set the Police Department’s budget above a minimum prescribed by the city charter, the agency is actually under the authority of Mayor Jacob Frey, who has been more supportive than the City Council.)

Hedberg said officers also fear the nightmare scenario of an encounter with a suspect that goes off the rails.

“It’s not that cops don’t wanna go to work, it’s the fact that they have such anxiety before going to work. Any call could be that call. Any call could make you go to prison depending on how the other person responds.”

Officers can walk into ambushes where someone is trying to get a “payday” out of it, she said.

“We don’t have the support, whatsoever. We’re automatically assumed guilty of everything all the time.”

Data show most officers don’t ultimately get disciplined after being accused of misconduct. Police Chief Police Medaria Arradondo recently took quick action, however, when he demoted a high-ranking deputy for saying the department needs to do a better job recruiting, lest it wind up “get(ting) the same old white boys” in a Star Tribune article. The police union denounced the deputy’s “racially charged comments.”

In addition to feeling beat up by elected officials and citizens, Minneapolis cops are “disappointed” with Arradondo, Hedberg said.

“He’s just not really communicating a whole lot to the police officers,” she said. (Given a chance to respond, a spokesman said Arradondo is not giving interviews at this time.)

Asked whether he has lost the support of the police, Hedberg said, “I think it’s difficult to maintain legitimacy if you’re not seen or heard from.”

He hasn’t gone to precincts as much as officers would like, and mostly communicates with them through YouTube videos, she said. The one time cops were definitely listening: When he went on national TV and said he was withdrawing from labor union negotiations. That “definitely frustrated the officers,” she said.

Council Member Fletcher said he wasn’t surprised to hear that, given the tension between the chief’s reform-minded approach and the resistance of rank-and-filed police.

Fletcher questioned who was really in command during the riots — the reform-minded chief or the union bosses.

Fletcher said police are being less proactive, “Because they didn’t wanna be in the next viral video.” That in turn has led to an 80% decline in traffic stops, he said.

“I don’t believe MPD leadership ever told them to stop doing traffic stops,” Fletcher said. “I think that was the federation deciding to pull back.”

Fletcher said Hedberg’s comments could be damaging to “what’s already a shaky level of trust and legitimacy in the department if it feels like the rank and file are not following the leadership.”

But the police union isn’t alone in its concern about the impact the “defund the police” movement has had on crime. Many north Minneapolis residents spoke out this summer against a proposed charter amendment that would have dismantled the Police Department and created a public safety alternative.

“This is a very, very intimate experience for me, and I’ve never seen it like this,” said Don Samuels, who served on the Minneapolis City Council from 2003 to 2015 and has lived in north Minneapolis 23 years.

He recently posted on social media about hearing 16 gunshots around 2 a.m., and calling 911 repeatedly.

“Hello Minneapolis City Council. Your city is hailing bullets. Do you care? Will you act?” he wrote. “Will you disband the shooters when you abolish the police?”

Hedberg is back at a collapsing bridge. This time it’s metaphorical, but in many ways no less important — she’s at the scene of the fractured relationship between citizenry and police.

“At some point you can look at the relationship between law enforcement and the community as a marriage that doesn’t have the option of divorce,” she said. “We can fight, we can argue, we can disagree, but we still have to find a way to work together. We can’t get a divorce. It just doesn’t work that way.”

(Deena Winter with the Minnesota Reformer contributed this report. It first appeared here in the MR.)